![red fox emblem on sweaters]()

Poldi (on right) with squadron buddies having some fun for the camera showing off their new sweaters with the "Red Fox" squadron emblem.

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Carlos Porter

29 July 1942: Today I’m back at our home port with my squadron leader and a small staff of technical personnel in readiness. I still have to do three days standby service and then I’ll be flying back to our home port and will be relieved by another squadron there.

Today I flew my first mission again. We attacked the port of Brixham again, where our leader was lost on 17 July. It was 16 hours 19 minutes when I flew through the harbor barriers, which consisted of 20 to 30 barrage balloons, with my wingman in a low-level attack, shot up a few small ships and aimed a direct bomb hit at the stern of a 4000 ton freighter. Unfortunately, I couldn’t see what effect it had, since their defenses kicked in quickly and the flak was being aimed very precisely. They made a lot of noise during the night when their bombs went off. As we flew off, we were pursued by a few Spitfires, but we were faster. On the high seas, I saw still another small tugboat. Our cannons spoke very clear language. We left it there, letting off a big column of smoke. So I was in the same harbor twice in the same day, today, in which I had already sunk one watch ship already. Today’s freighter was also seriously damaged, that’s for sure.

2 August 1942: I already know my way around the Brixham area pretty well, and the surrounding area. On 31 July, I was unlucky again. I flew from our home port (Caen) to St Andre, which is 125 km away, and forgot to lower the landing gears for both wheels when I was landing. So I landed on one wheel, that is, on the right wheel only, and the left wing. I was very angry with myself for making such a stupid mistake. So my plane is laid up for a couple of days for this piece of stupidity.

4 August 1942: Yesterday, I flew another mission that knocked me out like no other. First, I flew with my wingman in the vicinity of Falmouth on the western corner of southern England. The long stretch of water is already enough to wear you out. Then we ran into a lot of really bad weather, which got so bad over the English mainland that you could hardly see your hand in front of your face. Then we smoked a couple of small towns as reprisal for the terror attacks on small German cities.

On the return flight over England, we ran into the thickest fog; for good measure, a couple of electrical instruments conked out, so that I could no longer control my altitude, and I even saw a few telegraph poles go sailing right by my cabin window. Instinctively, I pulled back the control column and then, suddenly, I saw a couple of barrage balloons in front of me, which I was luckily still able to avoid hitting. What’s more, I had lost my wingman and was sure that he had flown into one of the mountains. He thought the same about me. When we landed again in our home port, we were happy to see each other again. After eating, we flew back to our usual home port. But I was shook up like never before.

12. August 1942: Yesterday I flew off with two planes to attack the city of Salisbury and destroyed the gas works, while my wingman destroyed the railway station. We got chased by a lot of Spitfires; they followed us to Portland, but everything was all right. I got the Iron Cross Ist Class for this mission, which I flew with an NCO, who flew the second plane. My wingman got the Iron Cross 2nd Class. The mission against Salisbury was carried out in strong wind, and a heavy swell at sea, too. We flew past the western tip of the Isle of Wight flying low, and then back again, surprisingly, in a big ring around the north of the city. So there were no air raid alarms going off in Salisbury and the streets were full of people and cars. There was a lot of traffic.

(From personal conversation with my brother, I think I remember that they were supposed to fly attacks against English cities as well from now on, in reprisal for the English bombardments of German cities, in which valuable cultural monuments were destroyed. Approval was even issued to damage Salisbury Cathedral if necessary, but my brother hadn’t the slightest intention of actually doing so. -W.W.)

![salisbury cathedral]()

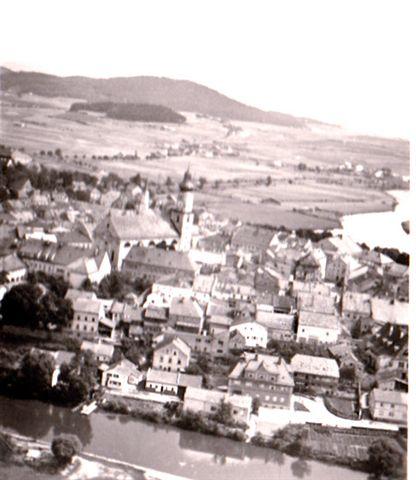

View from the air of Salisbury Cathedral and all that is built up around it.

I already recognized the city by its magnificent cathedral, where most of the English kings are buried; it’s an English national shrine. I also saw a big gas works, and immediately shot up the gas containers with my cannons, it was very easy to follow the tracers from my machine guns and could see exactly where they were going. It began to burn, then the bombs exploded behind us. My wingman attacked the railway station. He shot up the locomotive of an incoming train and aimed a direct hit on the train with the bomb. The whole city was completely surprised, there was no air raid alarm. The numerous barrage balloons were lying around the city on the ground. It all happened so fast. Flying low, I flew over a few flak positions and avoided them; it was all a little bit too quick for the chaps on the other side.

16 August 1942: I flew back over England again yesterday, too, and attacked the city of Worthing with my wingman, at around 18 hours. The flak was very accurate this time, they were already shooting as we approached. But that didn’t prevent us from finishing off a couple of big business complexes with our bombs. The weather over there was bad.

By the way, as for Dad’s question: my tonnage proportion amounts to 6200 tons (warship tons), up to now. This is equivalent to 17,360 British tons, but so far I’ve only had warships in my bombsights.

21 August 1942: On the 18th, we flew an attack against the Isle of Wight and bombarded the city of Ventnor. The row houses received a direct hit. They didn’t have time to set off any air raid alarms, either. So there was a lot of traffic in the streets. The flak only started firing when we had already turned around to fly off.

![Dieppe chart of 4 beaches]()

Click on image for enlarged view.

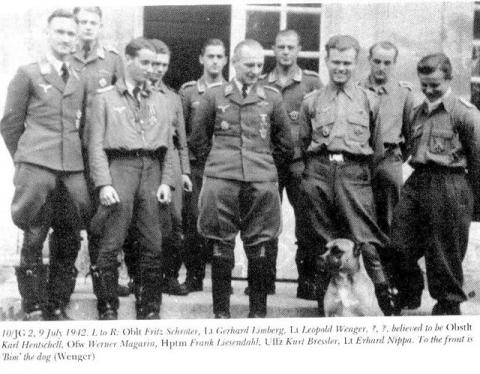

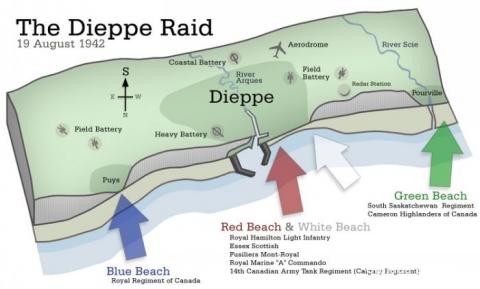

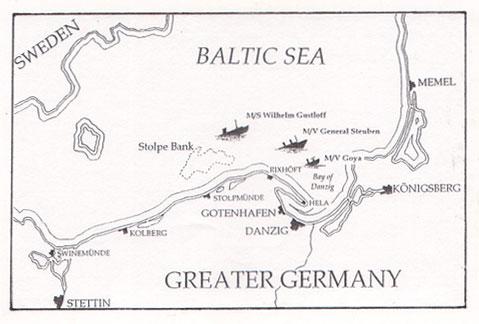

At dawn on 19 August, we got an emergency report that English were attempting to land. I was supposed to take off immediately with three planes on an armed reconnaissance mission. Since I figured there would be ships worth shooting at, I loaded my plane with especially heavy bombs. But I was very unlucky, as well as lucky at the same time. In rolling along to take off I broke the landing gear, and I slid across the grass right on my bombs: not a very pleasant sensation, when you think of the explosive power of those bombs or what they’re capable of doing during an attack and you can watch it, too.

![Dieppe location map]()

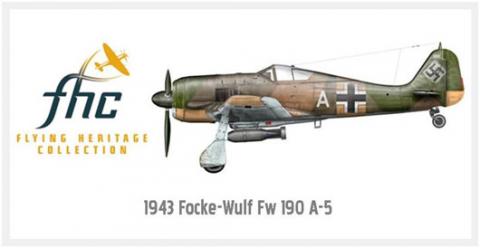

So I missed the first mission, took off from my second service port in a Messerschmitt 108 Typhoon to St. André to pick up my Focke-Wulf Fw 190, and then back to Caen. I was already afraid I’d get there too late, and the whole scare might be over by then. So my first mission began at 11 hours 30 minutes. When we reached Dieppe, the combat zone was completely befogged, cloaked with dust, smoke and dirt. The English fleet had fogged itself over completely. Muzzle flashes could be seen all over the place, there were fires burning all over the land from planes that had been shot down. On the beach lay burnt-out tanks which had been destroyed hardly 20 meters from the water right after the landing.

![Dieppe Raid]()

What Poldi Saw: Destroyed landing craft and tanks, along with dead Canadian troops at water's edge on Dieppe Beach.

There were a lot of fliers swimming around in their inflatable dinghies. At precisely 12 hours I set off with my unit on a low-altitude attack. At the same time, a German bomber just in front of us crashed vertically into the sea, not far away from us. That certainly wasn’t good for our morale! We went straight on ahead in the fog and suddenly, without seeing it, found the cause of all this fog, a very big English destroyer. We shot at it with all our machine guns and cannons, and dropped bombs on it at the same time. The heavy bombs detonated exactly underneath the stern of the destroyer. But then I got shot at with flak, all calibres. Too bad I wasn’t able to hang around and watch this fiery magic show any longer. The three other machines flying with me, damaged a couple more ships and shot down a Spitfire. In low-level attacks, we shot up the landing craft, which were stuffed with men. The effect was devastating, everywhere.

When I flew my second attack at 15 hours 30 minutes, the English had already "victoriously" withdrawn. The artificial fog was no longer much help to them. I attacked a second destroyer and, flying at low altitude, planted a very heavy bomb on the ship in the middle. During my attack, I was shot at very heavily, flak from the same ship. But when the bomb went off, there wasn’t a gun left firing. There was ONE detonation, simply magnificent! A black cloud followed the explosion and cloaked the entire ship. I then got chased around and shot at by many Spitfires and was unfortunately unable to observe any more of the final sinking. I got a lot of scale off the flak. Surface areas, motor plating and landing gear were all shot through. The cabin had two direct hits, but they got flattened out against the overhead armor. The mission was well worth it.

At around 17 hours, I started off on my third mission against the fleet, which was still trying to escape. Just before we got to Brighton, we finally reached a group of large landing craft, which had also set up barrage balloons. We attacked immediately. My bombs unfortunately bounced right over the ship and detonated about 10 meters from the ship’s side. Then I shot up the superstructure until it caught fire.

After this, the sea fight at Dieppe was over for us. Our squadron sank two destroyers, two big landing craft of 2000 BRT each, two watch ships and one Spitfire was shot down. One of our planes had to do an emergency landing near Dieppe. The squadron leader came to see us today and told us how it looked to him. The English were said to have been mowed down in heaps in front of the barbed wire entanglements by machine gun fire and killed by mines, which had been planted all over the place. The armored vehicles were mostly shot to pieces when they were still in the water. In any case, it’s a big defeat for the Tommies. Exactly what got sunk, will become clear over time. Let’s hope the English treat us to a repeat performance sometime soon, so we don’t get out of practice!

30. August 1942: I was over there again a few days ago, in the vicinity of Falmouth in Cornwall. You couldn’t see any ships, so they must have been keeping to their secondary targets. We blew up a few fine houses according to the motto “Never miss an opportunity”.

6 September 1942: On the 2nd, we bombarded the city of Ventnor on the Isle of Wight. They were shooting flak like mad. On the 3rd, I had to interrupt my service on the English coast, since the weather was too bad. That was near Dartmouth.

On the 4th, I flew with four planes in an attack on the West Channel. We flew over the city of Torquay, which had already been given a good thrashing by us on another occasion, and showed the city of Paignton a thing or two, demolishing trains, railway station and large houses, under heavy and accurate flak. One of our planes was shot down in flames (according to the casualty report, Uffizier Walter Höfer). At sea, we were attacked again, but without success.

On the 5th, we flew back home to our place, but on our way we came into sudden contact with the enemy, with 43 English four-motor bombers. Unfortunately, we saw them too late, and could no longer get into attack position, so there was nothing we could do -- after which we flew back over Rouen at 7000 meter altitude.

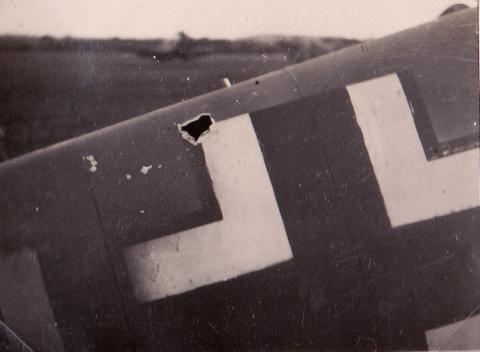

18. September 1942: Yesterday we flew a mission which unfortunately ended quite tragically. Together with my wingman, an NCO (according to the casualty report, Uffizier Walter Wandschneider) we were attacking a gas works in Worthing, low altitude flying, and exploded the bombs between two gasometers, which caused the whole thing to blow up. My wingman was busy bombarding the city. At exactly the same time, we came into contact with English planes. We were able to get away from them and reached the open sea despite heavy flak. In the middle of the Channel we were suddenly surprised by Spitfires, which attacked immediately. That’s how I lost my wingman. I saw him fall vertically into the sea, where I saw it hit the water, after which they started banging away at my machine, but I succeeded in getting away and reached home safely, although a 2cm shell projectile tore a hole in my gas tank, which caused me to lose so much oil the whole plane was like a sardine in oil. It was ghastly to see how fast it all happened and I couldn’t do anything about it.

![hole in fuselage]()

![hole in antenna]()

Damage to Poldi's plane -- holes in the wing and in the antenna

I was unable to fly in an even bigger attack with my squadron today, four ships were sunk at one time.

_____________________________

* In April 2001, I received an email from a Canadian Spitfire pilot, Barry Needham, who shot at my brother in aerial combat 59 years ago and caused the bullet hole in the gas tank of his Focke-Wulf FW190. His information is perfectly consistent with my brother’s log book entries. Later, I found a remnant of the 2 cm projectile removed from the fuselage by the mechanics, which our father kept as a souvenir, even engraving the exact date on it. -W. Wenger.

_______________________________

20 September 1942: It’s Sunday today and we have nothing to do. So I’m just sitting in my room in the castle where we live, where we already lived one time before. Even Louis XIV is supposed to have stayed here (a lot of things must have looked different then). [He means it's not all that comfortable in 1942 -W.W.]

We flew a mission in the West Channel yesterday. I flew with an NCO, who appears in the photograph enclosed with this letter. We flew together once before, at Salisbury, where he got the Iron Cross 2nd Class. We flew armed reconnaissance near Start Point. Off the city of Salcombe I sank four landing craft. I then shot up a group of tents, probably flak positions, and other buildings, with cannons and machine guns. The flak was very heavy and quite accurate. We flew through the valleys, at very low altitude, to make sure the clouds of smoke from the explosions were on top of us at all times. At the same time, my squadron leader put an anti-aircraft gun that was firing at us out of action in a direct approach attack. Two men fell dead, the third man ran away.

Yes, our squadron won recognition from all over the place for our successful defense of Dieppe. Our squadron captain (Oberleutnant F. Schröter) received the German Cross in gold; soon, he will probably get the Knight’s Cross, too. He’s already sunk and generally destroyed a whole lot of different types of ships, I can tell you. Our captain (F. Liesendahl) has now won the Knight’s Cross, somewhat late.

![pilots of the squadron]()

Pilots of the Squadron - 1942

![F. Schroeter]()

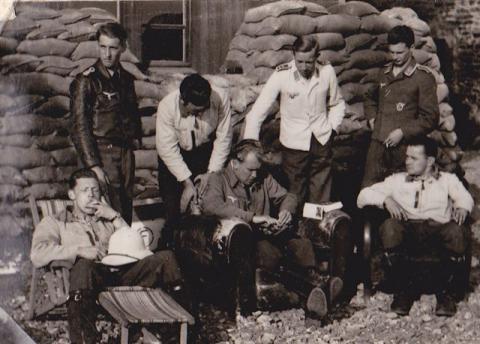

30. September 1942: The picture where I got the Iron Cross 2nd Class also shows our Squadron Commander (Oberleutnant F. Schröter) on my right [far left, with cigar, in the picture -ed]– most recently, he got the German Cross in Gold and the Knight’s Cross only a few days later. During my last mission in Bembridge (east coast of the Isle of Wight) we destroyed a couple of houses for the second time. We had the worst sort of weather over the Channel that you can imagine, had to fly around a couple of showers.

I was back in northern Europe the other day: in Belgium and also Paris, in a Messerschmidt Typhoon 108. Each time I had to pick up a Focke-Wulf FW190 and fly it back here.

6 October 1942: I flew another mission yesterday in bad weather. I wanted to fly to England near St. Albans, but the land was completely beclouded and so we bombed military objectives near Swanage. I hit an artillery position and damaged it very badly and my squadron leader sank 4 landing craft. Since it was pretty dark the red of the flak tracers looked very strange, really ghostly. The clouds over the sea were often only 20 to 25 meters high; but it was a trim little mission nonetheless!

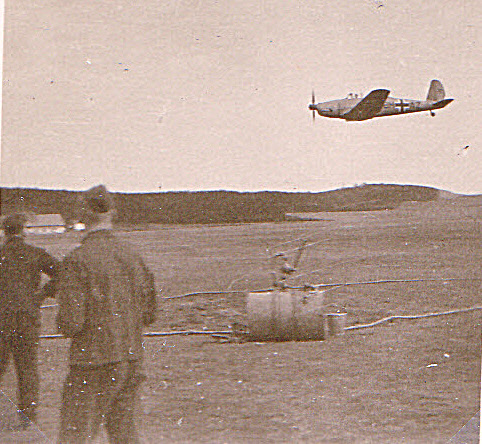

9 October 1942: These two photographs, taken during yesterday‘s mission show Dartmouth in the evening time, where I attacked a number of landing craft and damaged several with my wingman. We attacked the area – as you can see from the second picture -- flying very low altitude. There was no flak.

It was quite a different story this morning. This time, we went further south of Dartmouth towards Salcombe. Our target this time was landing craft and I sank two of them. (We‘ve sunk a total of 6 of them). Apart from that, we destroyed a stone bridge and a building. We didn’t have the usual 500-kg bomb with us, for the first time, but, rather, four 50-kg bombs. But they weren’t asleep at the anti-aircraft batteries today. There was a lot of lead flying around. During our flight back we got into a dog fight with two Spitfires, who were kind enough to accompany us all the way to the middle of the Channel. Then I landed on the former English island, Guernsey. It’s quite a beautiful country and we’d really like to have time to see it without so much excitement.

15 October 1942: Day before yesterday I was back in England again. This time we attacked the city of Shanklin on the Isle of Wight. I looked for something like a big four-story house and dropped my bomb very exactly, flying low, then watched the effect from a backward curve. I never saw anything like it before. First, nothing happened, then it was like somebody had turned on all the lights in the whole house. Then the walls slowly collapsed outwardly and a gigantic dark red column of flame burst out upwards from the rubble. I think there must have been something highly explosive stored in the house. My wingman also aimed a very beautiful direct hit, but the effect was nowhere near the same.

Yesterday evening, we were over there again, but in mid-Channel my wingman had to turn back due to motor damage.

11 November 1942: I‘ve already been away from our home eyrie for a week now and I’m sitting in a beautiful palace, which must have belonged to really rich people, in the region of Lille. (According to the log book it must have been Merville). After a little preliminary practice, we started out on a concentrated reprisal attack on Canterbury yesterday afternoon. It was like a Reichs Party Day! I’ve hardly ever seen so many machines in the air at the same time. We flew over the Channel flying at low altitude, northeast of Dover, and quite low straight to the city of Canterbury; in some places we had to fly through barrage balloons and then a pretty concert began. We dropped many thousands of kilograms of high explosive on the city at low altitude and shot up the houses with everything we had. The city was pretty much already destroyed anyway, but as we were flying away all we could see was a great, big, smoking, dusty area. Once again, the red and white of the flak and the tracers from our machine guns and cannons looked downright ghostly. On the flight back, anything that looked like a house or a haystack was attacked by many machines.

![Canterbury damage drawing]()

This looks like a painting, not a photograph, of some of the damage in Canterbury around the Abbey in 1942. The Germans did not bomb the Cathedral, which would have been a huge morale blow to the British, yet the Brits show no appreciation - only calling it "a miracle" and saying "10,445 bombs dropped during 135 separate raids destroyed 731 homes and 296 other buildings in the city."

Wherever you looked, you saw fires everywhere. The anti-artillery positions were silenced after the first fire storm. In the meantime, other machines shot down the barrage balloons over Dover, in flames. It was a picture you don’t see very often. There was no sign of English fighter planes anywhere. I guess it was just all too much of a good thing for them. We landed at our home port just as darkness was drawing in.

From the Channel to the Mediterranean

21 November 1942: (Istria) I’ve been sitting here on the Mediterranean coast for several days now, and I’m trying to get myself together. I didn’t get here by plane, but by train, since there’s nothing left of my plane except for a few bits of rubbish. During a flight over the French uplands on the 17th, my motor suddenly failed and I had to perform an emergency landing. The terrain was naturally no better than in other mountainous areas and the chances of success were not very high. Nevertheless, my belly flop would have almost been successful if the mountain meadow hadn’t been surrounded by a stone wall 2 meters high. Since I had no other choice, I had to go ahead with it. It was a bit nerve-shattering, but at least it was exciting. I lost consciousness immediately, but came to just as the machine or the piece of it I was still sitting in, finally came to a stop. To my great astonishment, to my right, next to me, 10 meters away, I saw the entire tail section of my beautiful plane standing upright, stuck in the ground. Now, I wanted to get out as quickly as I could, but the cabin wouldn’t break open. So I had to eject the cabin roof with the help of the explosive charge built in for that purpose. Then I climbed out, but could not climb onto the wing, as is usually done, because there was none there; it had broken off. I was slowly running out of strength.

Fortunately two Frenchmen came along, who grabbed me underneath the arms and dragged me to a car standing not far away. They took me to the Gendarmerie in the next village. The French officer drove with me to the nearest hospital. There I was held down on a table and a strange sort of doctor began to wash, and stitch up my head. Finally that was over, and I had to spend a night in this odd little hospital. All my bones were hurting and the mosquitoes wouldn’t let me rest during the night. You can imagine how happy I was when a German doctor came to pick me up the next morning and took me to Lyon, where I was lodged in a hotel, since there was no military hospital at that location yet. So I was naturally anxious to get back to my unit as soon as possible and see our military physician. I got my wish during the night of 19 November (Poldi‘s 21st birthday -W.W.). In Lyon, my personal property was returned to me after being held for safekeeping by the French Gendarmerie. Only my briefcase looked the worse for wear, all torn up, with all the most valuable items missing: camera, fountain pen, Combat Honor Roll Clasp, a few tablets of chocolate, irreplaceable souvenirs. I miss these mementos, which can no longer be replaced.

Now I’m sitting on an express train, with the rest of my things, travelling to Marseilles. I arrived at around 22 hours, and was immediately picked up by our special deployment officer, an Oberleutnant, since I had been able to inform my squadron of my arrival; this was the beginning of an endless overnight journey. This drive, under a full moon, would have been certainly very beautiful under normal circumstances, but all my limbs were hurting and I couldn’t move. We arrived early in the morning, at about one o’clock, and I finally got to bed.

During the next day my headache got so much worse that I suddenly had to visit the doctor. When he removed the head bandage, he saw that the skin on my forehead was full of pus, so back we went again, in the car, 60 kilometers on bumpy French roads, to the nearest military hospital. There my forehead wound was opened again and the stitches were removed (I’m getting used to it!). Then began the skull-throbbing trip back to our new billet.

Today, my skull is all right again, at least so far. My wounds have all crusted over and my ear is growing back together in one piece. My eyes are still a bit red, but I can see all right. The only thing is that, now, other parts of my body are hurting that I hadn’t noticed in the first few days after the accident. The pains in the small of my back have gotten so bad that I can hardly move. But in the end, even that will disappear.

Where we’re stationed there is a airfield with a unit of the French Air Force stationed on it. Relations between the two units are very cool. We don’t trust each other at all. The region is on the coast, and something entirely new for me. There are steep, rocky mountains and everything looks like a stone desert. There is almost no construction on this terrain. A few vineyards and fairly large olive groves are all you see. Everything the French do is one huge pigsty, including the lodgings. The sanitary installations are in a catastrophic condition. It is certainly no accident that this country lost the war. Among the French, soldiers are considered second-class citizens, and are treated like it. I can’t understand this attitude.

The weather here would be good, if it weren’t for the wind. I think they call it the mistral. So far, I’ve only seen blue skies, but nevertheless it is surprisingly cold, even in the sun.

I’m doing everything I can to get my poor bones back in shape again, to see the region around here from the air. Unfortunately, it will take some time before this is possible. I’m glad the doctors haven’t told me to keep to my bed, that was what I feared most.

28 November 1942: There’s been a small change where we are concerned. The disarmament of the French troops. They were completely surprised when the announcement was made—at dawn. Most of them were relieved, since it meant they would be released from service and could remain in France. To us, it is rather a comfort not to have these fellows hanging around in our vicinity. As for my physical condition, I’m getting better—so far, so good. My right ear has healed. The scabs on my face are gone now, thank God. My forehead wound is not entirely healed yet. The doctor told me today that I must be patient for a while. They also washed my head. I couldn’t stand it anymore. My skull was itching all over from being bandaged up all the time. Now at least that’s over; the bandage is considerably smaller now. I don’t have to go to be bandaged up every two days any more, either.

2 December 1942: We’re moving about again. I got a medical attestation, which was issued—thank God—after a few formalities. Magnificent, I can fly again! So we’re leaving the Mediterranean coast. After an interesting flight through the Rhone valley we landed in Dijon after eighty minutes, but we had to stay put for three days due to the bad weather. I went to the doctor today and my head bandage was finally removed. I only have to wear an adhesive plaster for a while yet. All that remains is for my hair to grow back and for the red specks in my eyes to disappear. The main thing is, that flying is no longer a problem for me.

5 December 1942: I’ve been back at my old home eyrie for two days now. Since we couldn’t take off from Dijon because of the bad weather, I had a chance to see the city and was very pleasantly surprised. The city is very clean and doesn’t really look very French. Compared to the other places we’ve seen in France so far, for France it’s a rarity. We flew here from Caen. The situation in southern France was very changeable, but since no real combat missions could be flown the change wasn’t much to speak of, perhaps a chance to rest. In any case, we’ve seen something new, and that is worth something, after all. It sounds like a joke when I say that it is warmer here than on the Mediterranean coast, but it’s really so (influence of the Gulf Stream). I had to wear my sweater, it was so cold I couldn’t stand it.

I saw the doctor again today, it seems I’m now completely well again. The scrape on my head looks better already, almost completely healed and I can take the plaster off in three days. It’s just that the doctor doesn’t want me to fly any combat missions. But in a couple of days it will be all over. I’m only glad I haven’t missed anything important in these three weeks. We made an advent wreath that looks really good today. Now we’ve got to go looking for a fir tree or a spruce, since these trees are rather rare here.

10 December 1942: I’m feeling well again and I’m completely cured. Don’t need any more plasters. This is the first time I’ve seen things in proportion, since it all seemed more serious than it was. The scrape on my head is minimal. You can’t even see that my ear was injured at all any more. That I can fly without restrictions now is the best proof that I’m 100% OK.

Only an answer to your question: I didn’t have my other things with me during my emergency landing, but, rather in my luggage, which was in a transport vehicle on the ground. Naturally I was flying all by myself, but in this case nobody could have helped me anyway. It’s not a question of negligence or poor flying either, it must have been a motor fault; that can happen. Of course, nobody is criticizing me for anything. The commander (Major Günther Tonne?) also thought that I should have bailed out immediately, but I was flying so low I couldn’t.

It’s quite impossible to get a rest and relaxation furlough and I wouldn’t even think of it. I feel quite healthy, too. And then, I wouldn’t want to take a father away from his family at Christmas time by taking his furlough, although I can’t imagine anything more beautiful than spending Christmas with you.

15 December 1942:I’m feeling well, only the left eye is red. I still had my ring and my pistol with me. Nobody’s taking those two things off me; they’d have to kill me first. I flew again today and dropped some practice bombs, so as to keep in practice.

25 December 1942:Our Christmas Eve went a little bit like this: first I sat by the radio and at about 20 hours I celebrated, together with the whole squadron. They put a little music together, the mess hall was decorated really nicely. There was a murderous big piece of pork roast for everybody and drinks, so enough talk about my luggage.

30 December 1942:It’s gotten a little bit colder now, but the weather has gotten better. One of our squadrons carried out a foray against the English coast yesterday and shot down two Spitfires after dropping some bombs on an English city. Unfortunately, I couldn’t be there with them. We also chucked a couple thousand kilos of bombs on them this morning. Their anti-aircraft defenses were taken completely by surprise; they were shooting very badly. Then we flew over a stretch of English countryside and shot up a few houses on the way back.

- End of 1942 letters -

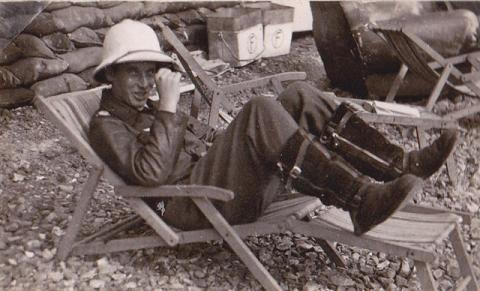

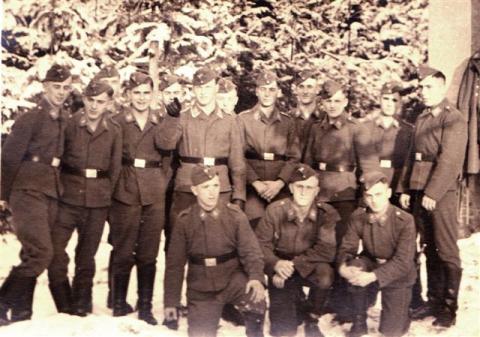

Marching the recruits at Oschatz, 1939

Marching the recruits at Oschatz, 1939